“What I propose, therefore, is very simple: it is nothing more than to think what we are doing.”

Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition

Courses at Smith College

I teach courses in the history of political thought, democratic theory, race & politics, social movement studies, Black political thought, and anticolonial political thought.

-

This introductory lecture course provides an introduction to the history of political thought, and more broadly, to a history of what it means to think politically — about the nature of our collective lives, about the rights and obligations of rule, about the limits of political power, about the virtues and vices that define the practices of citizenship and leadership, and about the forms of violence, domination, and exclusion that have often underwritten political communities of all kinds. Political philosophers stretching back to the ancient world have long examined and debated what it means to study politics— the kind of knowledge proper to politics — as well as the kinds of values, political regimes, institutional forms, laws, and economic systems that best facilitate “the good life” for human beings.

Political thinkers did not ask these questions in a vacuum, or disconnected from the political contexts in which they lived. Indeed, the history of political thinking is a history of thinking with and through crises, generated by conditions of tyranny, war, upheaval, conquest, and domination. Now, as we live through crises of our own — a global pandemic, ecological crisis, and the delegitimization of democracy to name but a few — the project of thinking politically in times of upheaval is one we share with thinkers from Plato and Aristotle to WEB Du Bois, Simone de Beauvoir, and contemporary philosophers like Charles Mills.

-

In the contemporary world, democracy is often considered not merely a form of government or one type of regime among many, but the very condition of political legitimacy. But what exactly do we mean when use the term “democracy”? Is it an institution, an ideal, a practice, a problem? Despite the global appeal of democracy, there is no clear or definitive answer to the central question of what democracy means; as a concept, it remains an “essentially contested.” Is democracy an intrinsic good--inherently linked to ideals like liberty, equality, autonomy, and the public good? Or is it is merely an institutional arrangement that helps achieve other valuable ends? Does true democracy require direct rule by the people, or do representative structures better encapsulate the meaningful aspects of democratic governance? How is democracy implemented, what does it require to function, and what are its problems? What is its relationship to capitalism?

This lecture course offers a broad introduction to core themes and concepts in democratic theory. Through the semester, we will explore the origins of the idea and practice of democracy, and track how the meaning of democracy has changed over time and across contexts. We will consider the rights, responsibilities, and practices that define democratic citizenship, and interrogate the practical mechanisms and processes that ought to be used to institutionalize democracy – from electoral competition to representation to contrasting models of participation, deliberation, and dissent. We will contend with different approaches to thinking about the relationship between democratic rule, the private sphere, civil society, and the economy. And we will examine how different theoretical articulations of democracy confront problems of exclusion, domination, and inequality. This course grapples with these issues by exploring the complex and contested meaning of democracy stretching from ancient Greece to the present.

-

Taken literally, democracy (from the ancient Greek, demos [the people] and kratia [power, rule]) means “the people rule.” But what does it mean for the people to rule, and who are “the people”? These questions, central to democratic theory, emerged with particular urgency in anticolonial and anti-imperial movements across the globe, amidst diverse struggles for decolonization and self-determination. Mobilizing against decades, and in some cases centuries, of violently imposed imperial rule, economic exploitation, political domination, and social fragmentation, anticolonial and anti-imperial thinkers and movements attempted to reimagine the shape of a democratic world after colonialism.

This course approaches the core questions of democratic theory from the perspective of anticolonial and anti-imperial political thought. What is democracy, and why is it valuable—not in general, but as a way of organizing postcolonial political society and as a horizon of future possibility? What does it mean for the people to rule themselves when ruling colonial ideology denied the capacities of the colonized for self-governance? Should the institutions of postcolonial and post-imperial democracy—the mechanisms through which the people will exercise political power—mirror those of European representative democracy, or should they take another form? How might particular democratic practices, institutions, or processes counteract structures of the structures of imperial and colonial rule? Is domestic democracy sufficient for safeguarding popular self-determination if the international political and economic system is dominated by imperial powers? Can postcolonial democracy coexist with capitalism? Can it exist without it?

Course readings will be drawn from a wide range of anti-, post-, and de-colonial thinkers from around the world, mostly through the late 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries, including both texts from figures within anticolonial movements as well as contemporary work in postcolonial and decolonial political theory.

-

The ideal of United States citizenship has long laid claim to universal inclusivity and openness: citizenship, as both a legal status and a political-cultural identity, is supposedly accessible to all individuals within the polity. Yet the history of U.S. citizenship is one marked by the colonization, domination, and disenfranchisement of various groups defined as racially other, and thus outside the bounds of citizenship. How do we understand the coexistence of claims to equal democratic citizenship in the U.S. alongside the historical realities of enslavement, extermination, and other forms of racial violence? What does it mean to be a U.S. citizen, and how as that meaning been shaped by the formation of race across space and time?

This colloquium interrogates these questions by examining three modes about thinking about the United States as a racialized space: as a slavocracy; as a settler colony; and as a "nation of immigrants." Through readings in political theory, history, sociology, American Studies, Black Studies, and Indigenous Studies, we examine dimensions of U.S. citizenship that emerge with, through, and against the creation of racial hierarchies: citizenship as a legal status, as a political-cultural identity, as civic responsibilities and cultural norms, and as a particular arrangement of institutional practices that define who is “inside” and “outside” the political community. Throughout our discussions, we will also examine how dominated and oppressed racial groups have mobilized by both adopting and challenging prevailing notions of what it means to be a citizen.

-

This seminar in political theory examines the theory and practice of dissent, exploring both distinct categories of practice (satyagraha, self-defense, riots, strikes, sabotage, hunger strike) as well as different theoretical lenses for interpreting what those practices express and reveal about political life (vulnerability, affect, refusal, power and powerlessness, material privation, biopolitics/necropolitics, waywardness). As we progress through the course, we will ask: Why (and how) do people mobilize collectively in protest? How should we understand varied modes of resistance, from nonviolent direct action to riot to sabotage? What effect do different forms of resistance have, and what is their political value or political pedagogy? Through this course, we will engage these questions by reading and discussing contemporary texts from political theory and the interdisciplinary study of dissent and resistance, as well as works by practitioners of forms of dissent.

-

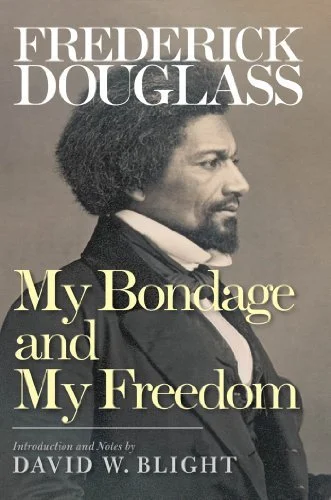

In his essay "Contours of Black Political Thought," political theorist Michael Hanchard identifies two broad purposes animating Black political thought: First, he argues, it is a "practice of theorization and conceptualization" that developed in the wake of and in response to the world-destroying and world-constructing forces of "apartheid, colonialism, and racial slavery." Second, and consequently, Black political thought aims to "situate racism and race-making at the core of the projects associated with Western modernity." Black political thought is, he clarifies, a "practice of reconfiguration, identifying the presence of racism, and black subjectivities in scholarship and histories where their presence has been minimized or altogether ignored" (2010, 512)-- an attempt to "[speak] things unspoken" and a tradition of learning "to see (theorin) differently" (513).

This seminar will engage with and partake in this theoretical tradition of reconfiguration and participate in the practice of learning to see categories of Western political thought--freedom, self-determination, subjectivity, legitimacy, law, labor, justice--in new ways. Centrally, this course will take up the study of African American political thought both as political thinking generated by concrete historical experiences of enslavement, colonialism, violence, and resistance/resilience; but also, as political thinking that engages, challenges, and fundamentally shapes the central conceptual categories of modern political theory.

As embedded intellectual responses to the world built by slavery and colonization, this course will take a global view of African American Political Thought — exploring how Black political thinkers responded to political dynamics within as well as beyond the United States, and envisioned forms of liberation that required building entirely new worlds. We will also encounter African American and Black Political Thought as a tradition that is alive and ongoing by engaging with canonical and historical works as well as new ones by contemporary theorists.

Courses at University of Chicago

As a research postdoctoral scholar, I designed and taught two new courses in the Department of Political Science: a seminar on civil disobedience and a colloquium on race & citizenship.

-

This course will examine relationship between race and the discourse, concept, and practice of citizenship in the United States. Throughout the course, we will interrogate how ideologies and experiences of race and citizenship have constituted each other over time, producing particular forms of politics – and enabling forms of unequal political belonging to coexist with claims to equal citizenship and democratic principles. [Fall 2016]

-

Do we have an obligation to obey the state? If institutions, laws, and public authority are democratically organized, what do we owe the state and our fellow citizens? Are we morally bound to obey even unjust laws? What kinds of social protest, disobedience, and resistance are justified? What marks the boundary between citizenly disobedience and more militant forms of resistance and rebellion? Is violence ever legitimate? This seminar will engage with these questions by reading classic and contemporary texts from both philosophers and practitioners of forms of disobedience and resistance. As a course in democratic theory, we will be particularly concerned with how disobedience and protest relate to our ideas of what democracy requires of governments as well as citizens, with a view toward constructing a rich, context-sensitive, and nuanced account of political responsibility and judgment that can be used to evaluate disobedience, resistance, and protest in the political present. [Spring 2016]

Courses at Yale University

I served as a Graduate Teaching Fellow in the following courses. WI denotes courses that were “writing intensive.”

While at Yale, I also worked as a trained writing tutor for English as a Second Language and other special needs undergraduate students.

-

Professor Seyla Benhabib, Fall 2011. This is an advanced lecture and discussion course in the 20th century continental political thought. I taught two discussion sections and delivered a guest lecture.

-

Professor Ian Shapiro, Spring 2012. This is an introductory lecture and discussion course in moral and political philosophy covering a range of topics. I taught one writing-intensive discussion section.

-

Professor Karuna Mantena, Fall 2012. This was an introductory lecture and discussion course on the theory and practice of nonviolent political action, focused primarily on the thought of MK Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr. I taught one discussion section and delivered a guest lecture.

-

Professor Elisabeth Wood, Spring 2013. This was an intermediate lecture and discussion course in social movement theory and the political sociology of movements. I taught one writing-intensive discussion section.

-

Professor John Wargo, Spring 2015. This was an introductory lecture and discussion course covering a range of topics in environmental policy, politics, and law. I taught two discussion sections.